Kate Alexander Shaw

Based on a Research Article by Kate Alexander Shaw, Joseph Ganderson and Waltraud Schelkle

Full publication: ‘The strength of a weak centre: pandemic politics in the European Union and the United States’, Comparative European Politics, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00328-6

New research from the SOLID project shows how the EU’s fragility became its strength during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In early 2020, when the Covid-19 crisis struck, some commentators asked if this might prove a ‘Hamiltonian moment’ for the European Union. Faced with a challenge on this scale, they suggested, perhaps the EU would recognise the need to strengthen its institutions, centralise some real fiscal firepower, and take a leap towards becoming a mature federation in the style of the United States. This kind of commentary fit into long-running critiques of the EU as an ‘incomplete’ federal system. According to this argument the EU’s central institutions cannot drive through optimal policy solutions, instead ending up with whatever half-baked deal can be agreed by the over-powerful yet disparate Council of member states. These incomplete bargains often contain the seeds of the next crisis, leading to an endless cycle of ‘failing forward’. Maybe a pandemic, which would not respect national borders, would break the chain and take Europe’s weak-centred federation to the next level?

In our new research for the SOLID project, Joseph Ganderson, Waltraud Schelkle and I tell a different story. By comparing the performance of the EU and the US during the pandemic (a rare parallel stress test of both political systems at once), we show that centralised power does not guarantee good crisis policy; strong federal structures have their own problems, which may be exposed during a crisis episode. In fact, the EU’s weak-centred political system turned out to have surprising advantages in the Covid-19 crisis, particularly when it came to managing the political relationships between states, and between tiers of government. Our research finds that the very weakness of the EU as a political system helped spur its leaders into action during the pandemic, incentivising them to find joint solutions not just to confront the virus, but to preserve the EU itself.

The EU’s weak-centred political system turned out to have surprising advantages in the Covid-19 crisis, particularly when it came to managing the political relationships between states, and between tiers of government.

Pandemic politics in Europe and America

In Europe, things did not get off to a good start. Italy suffered the continent’s first major outbreak of Covid-19, and as early as February 28th it turned to its European neighbours for relief through the EU’s Civil Protection Mechanism. Italy’s call for help got no response; meanwhile France, Germany and the Czech Republic, all big producers of medical equipment, imposed export controls to prioritise domestic access to PPE. Public opinion in Italy turned sharply against the EU; polling in April 2020 suggested nearly 50 per cent of Italians would vote to leave in a referendum, up from about 30 per cent before the pandemic. Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte was explicit about the political threat posed by the crisis, warning that the EU itself would be at risk if it did not come together in solidarity.

The European Commission responded with a combination of practical and political action. While it had very limited powers to assist Italy’s pandemic response, it acted to prevent price gouging on PPE exports and diverted EU funds to pay for repatriation flights and medical equipment. On 1 April, Commission President von der Leyen published an article in La Repubblica apologising for Europe’s failure to show solidarity in the first weeks of the outbreak, and promising that the EU would now be “rallying to Italy’s side” because “we can only defeat this pandemic together, as a Union”. This was more than mere rhetoric; that July, the European Council agreed a €750bn package of support for member states’ economic recovery, to be provided through a combination of loans and grants. The deal also broke new ground by using joint debt to finance a common crisis response.

Pandemic politics in the United States had a different trajectory. The first outbreaks were concentrated in New York City and then the wider Northeast, requiring an already-sceptical Republican President to coordinate the early response with mostly Democratic state governors. To begin with, it appeared that the pandemic would generate a rare bipartisan response; the CARES Act passed in March 2020 with support from both Republicans and Democrats, providing an economic stimulus package worth $2.2 trillion.

At the same time as this economic deal, however, the response to the health crisis showed how contentious US pandemic politics would become. As in Europe, protective medical equipment was in short supply; in contrast with the European Commission, the US federal government had considerable powers to commission its manufacture, and deep pockets to pay for it. State governors including New York’s Andrew Cuomo called on the President to step in, for example by making use of the Defence Procurement Act to divert manufacturing capacity to producing emergency medical supplies. President Trump largely shunned these requests, telling the states to “try getting it yourselves”. The result was a procurement free-for-all in which individual states had to compete against each other, and even against federal agencies, for the same consignments.

In America, these early problems did not serve as a wake-up call, and the fragile bipartisanship that had passed the CARES Act soon fell apart. Whereas Europe’s rocky start had prompted a solidaristic u-turn, political actors in the US became ever more divided as the crisis went on. By the summer of 2020, amid growing acrimony about whether federal funding would be provided to hard-hit states, relations had deteriorated to the point that Cuomo accused President Trump of “actively trying to kill New York City”, while Republican lawmakers railed against “blue state bailouts”. Where European leaders had made a show of rallying together, in the US both federal and state politicians were more likely to make a show of opposing one another.

How political systems shape crisis politics

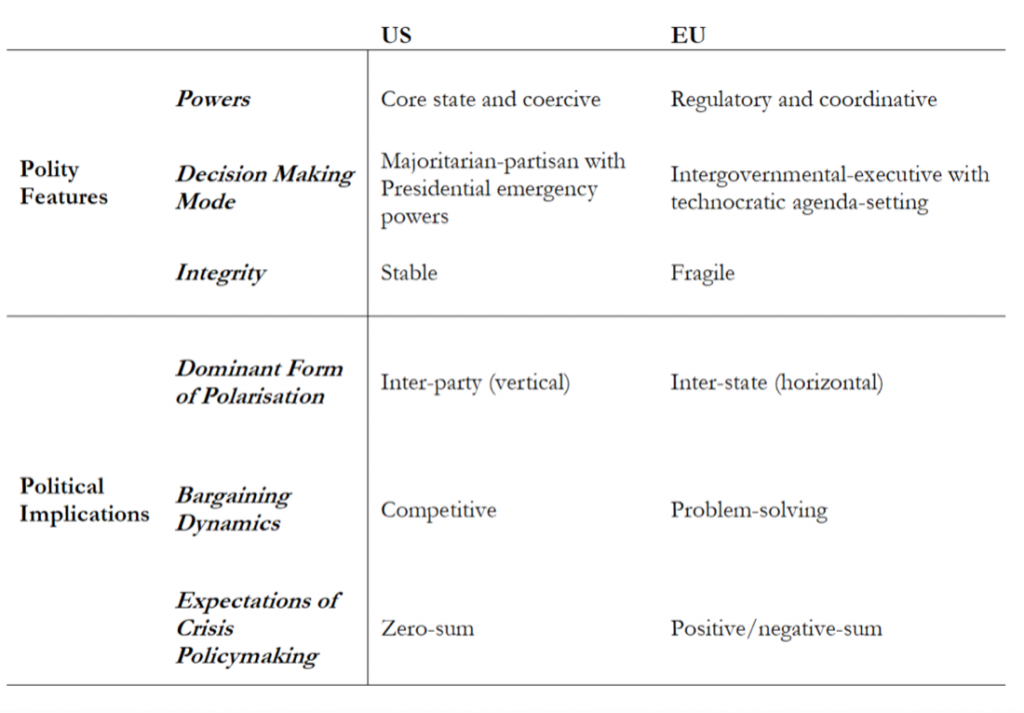

It might be tempting to reduce pandemic politics to the qualities of individual leaders in the EU and US in 2020. The EU entered the crisis with the experienced premier of its largest member state, Angela Merkel, in the business of securing her legacy; the US had Donald Trump in an election year. Yet while the Covid response continued to be highly contentious in the US under President Biden, the EU remained committed to projecting unity even after Merkel’s departure, suggesting that there is more to it than the competence and leadership style of individual politicians. Above all, we find that it was the structural features of the two systems which incentivised cooperation between tiers of government in Europe, and conflict in the US. These key polity features and their political implications form the framework of the paper, and are summarised in Table 1.

We find that it was not individual leaders that made the crucial difference; above all it was the structural features of the two systems which incentivised cooperation between tiers of government in Europe, and conflict in the US.

There is no doubt that the US central government is ‘stronger’ than the EU’s central institutions in terms of formal powers, institutions, and budgets. But if we broaden our definition of strength beyond this direct power, and think about how decisions are made and why, the supposed weakness of the EU looks rather different. A key difference between the two systems is their decision-making processes. In the US these are largely majoritarian, with some executive powers for the President; in the EU decision-making is intergovernmental, requiring consensus in certain circumstances. The European Council in July 2020 went on for a record-breaking five days, keeping leaders gathered together until a budget deal could be reached. In the US, Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan foundered on Republican opposition and the veto power of a single Democratic senator. In a crisis situation, the strength of the US federal government could not overcome political deadlock, while the EU style of decision-making incentivised cooperation.

Most crucial of all, in our view, is another underestimated feature of the system: the EU’s awareness of its own weakness. The pandemic began just weeks after the conclusion of Brexit, which had shown for the first time that EU membership is not a one-way gate. The early weeks of the pandemic raised the spectre of Italexit, and saw panicked member states retreating from fundamental principles of open borders and open markets. In such a climate, the EU could not afford to take itself for granted. The EU’s fragility thus became a strength during the crisis, motivating member states and the Commission to overcome distributional conflicts and work to shore up the centre when it was most vulnerable. We call this polity maintenance – that is, the politics of holding together. It is different from simple crisis management because it overlays the immediate crisis (in this case, a twin health and economic crisis) with a political meta-objective: that of holding together the EU itself.

In the United States, this polity maintenance logic was noticeably absent. Without the prospect of state secession and disintegration, the US could take its continuity as a nation for granted, allowing politicians to indulge in partisan blame games and pitting state and federal authorities against each other in zero-sum battles over power and resources. Even the January 6th riots challenged the quality of American democracy, but not its boundaries. Had Europe’s member states behaved in this way they could have risked the EU’s political disintegration.

The strength of a weak centre

It is important to be clear about the limits of this conclusion. We do not suggest that the weakness of the EU’s formal powers is irrelevant; in functional terms weakness is still weakness, and the EU still lacks the tools to confront certain policy problems effectively. Part of the success of its pandemic response was achieved precisely by strengthening the centre, as in the budgetary compromises agreed in 2020, or the channelling of new funds to health spending and vaccine procurement. But in important respects, it was the very political fragility of the EU that proved its greatest strength in this crisis.

The comparison with the United States, where even a once-in-a-century public health crisis could not overcome entrenched partisan conflict, throws Europe’s performance into sharper relief. Polity maintenance in a crisis cannot be guaranteed by pooling resources at the centre; it also relies on political commitments that can be activated in the face of a common threat. In this example, the European polity became an example of the strength of a weak centre; those who call for Europe to adopt a stronger federal structure should perhaps be careful what they wish for.