Marcello Natili, Fedra Negri and Stefano Ronchi

Based on a Research Article by Marcello Natili, Fedra Negri and Stefano Ronchi

Full publication: ‘Widening double dualisation? Labour market inequalities and national social policy responses in Western Europe during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic’, Social Policy & Administration, Online First: https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12814

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing divides and socio-economic risks. This is particularly worrisome in Europe, where the Great Recession and the sovereign debt crisis had already led scholars to speak of a ‘double dualisation’ (Heidenreich 2016). Did the COVID-19 pandemic also worsen income inequalities between insiders and outsiders and between core and peripheral countries?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing divides and socio-economic risks. This is particularly worrisome in the Old Continent, where the Great Recession and the sovereign debt crisis had already left scars that were so visible as to lead scholars to speak of a ‘double dualisation’ of Europe (Heidenreich, 2016; Palier, Rovny and Rovny, 2018). This term is used to indicate an increase of inequality at two distinct levels. Firstly, at the individual level, the reference is to the so called dualisation of European labour markets: the growing divide in terms of employment and social security between more sheltered ‘insiders’ (i.e. workers hired under open-ended contracts) and more precarious ‘outsiders’ (i.e. workers hired under atypical contracts and less social protection guarantees, despite being often exposed to unemployment). Secondly, at the country level, the second layer of double dualisation regards the socio-economic divergence between ‘core’ to ‘peripheral’ EU member states, with the former characterized by better macroeconomic performance, standards of living and labour market opportunities. Needless to say, cross-country inequality increased considerably in the decennium horribilis that followed the sovereign debt crisis.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe, double dualisation was well underway. The COVID crisis came as an unexpected shock, and thus constitutes a test-bed to investigate whether the pandemic has been a catalyst of pre-existing labour market and territorial divides or whether it provided national governments with an opportunity to address and possibly soften such divides through emergency-policy responses. Three questions guided our recent research on this matter: did the COVID-19 pandemic worsen income inequalities between insiders and outsiders? And between core and peripheral countries? Were the emergency measures enacted by national governments successful in handling, or at least containing, such inequalities?

We addressed these questions by combining the analysis of survey data on seven European countries with qualitative case-studies on the policy responses to the pandemic adopted in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands—three countries that were selected to cover the core and the southern periphery of the euro area as well as to compare emergency measures adopted in three different welfare state contexts.

To begin with, we took advantage of the survey ‘The Economic and political consequences of the COVID crisis in Europe’ to look at the subjective perception of income loss among European citizens during the first wave of the pandemic. The survey, devised in the framework of the SOLID ERC Research Project, was fielded by YouGov in June 2020 in seven European countries: France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Short-time emergency policy responses in countries with traditional insider-biased welfare arrangements further penalised outsiders.

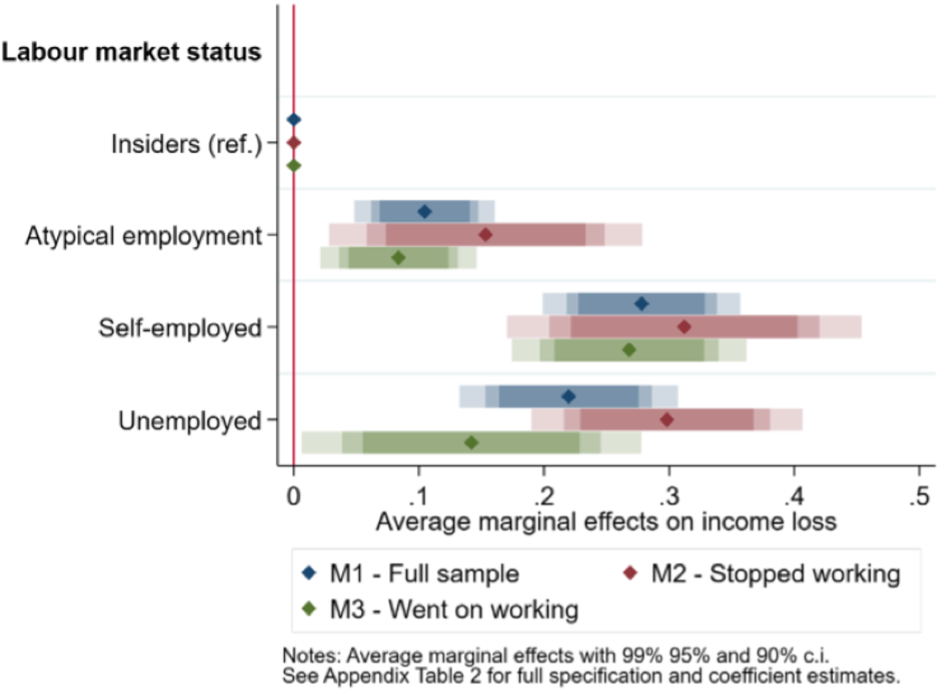

Results show that, in the aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic, outsiders were significantly more exposed to major income losses than insiders across the seven countries. As shown in Figure 1, being an atypical worker (vs. being an insider) increases the predicted probability of having experienced a major income loss during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic of 10 percentage points. The pattern is stronger (+22 percentage points) for the unemployed, and even more so for the self-employed (+28 percentage points). The latter—and in particular solo self-employed, who constitute the large majority of self-employed respondents in our sample—may have perceived an even stronger penalty due to the unprecedented nature of lockdown measures, which indeed exposed important gaps in the social protection that increasingly relevant category of outsiders (Spasova et al., 2021).

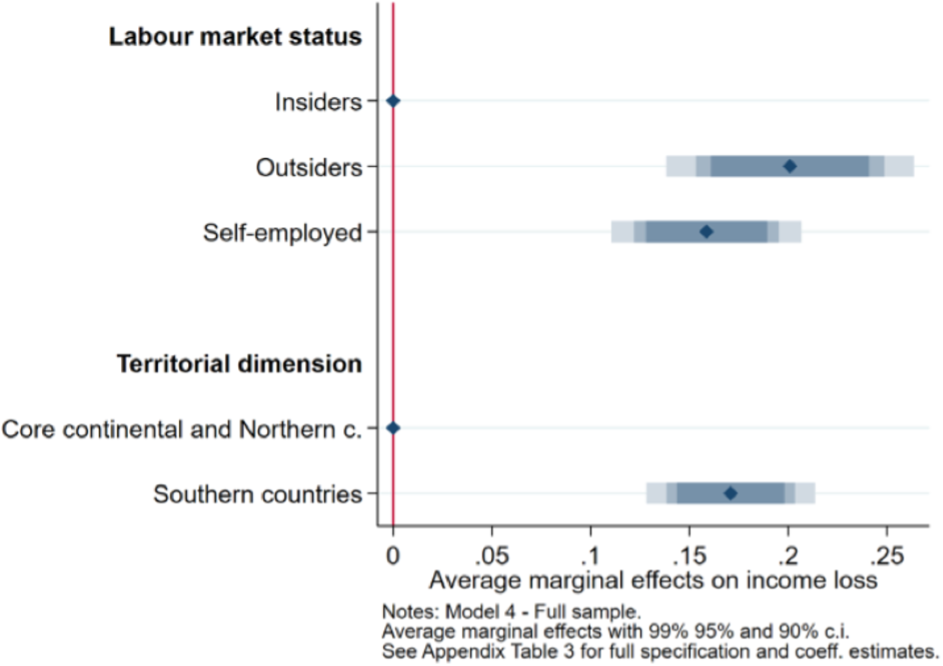

Moving to the core-periphery divide, income losses seem to have been more marked in the southern periphery than in continental and northern European countries. As shown in Figure 2, people residing in Italy and Spain are about 17 percentage points more likely to have suffered a major income loss after the first wave of the pandemic than people residing in the continental or northern European countries of our sample.

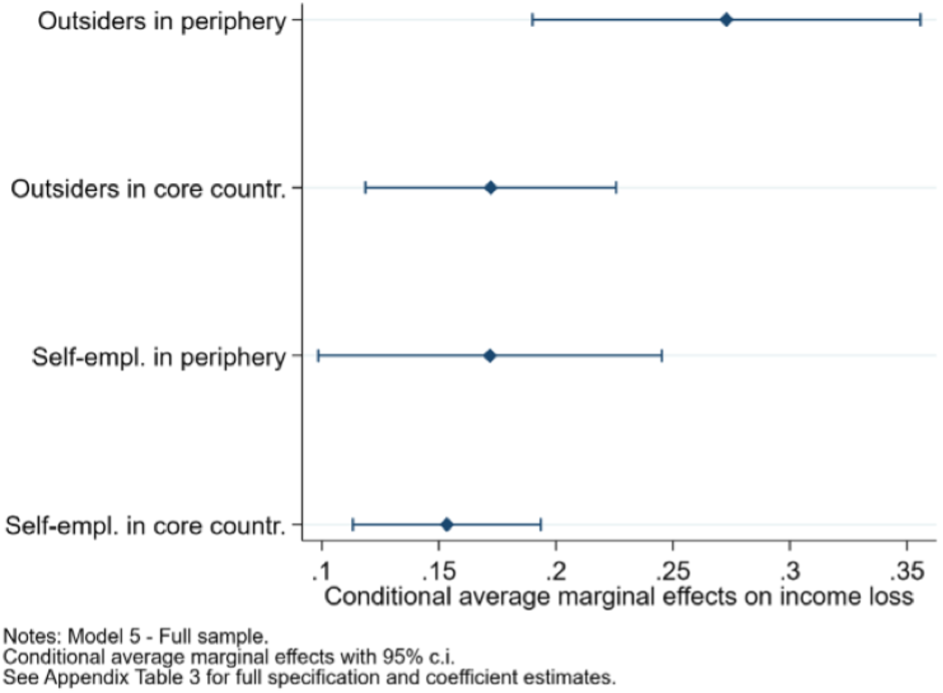

Furthermore, labour market and territorial divides apparently reinforced each other. Figure 3 shows that, while in Italy and Spain outsiders are 28 percentage points more likely to have suffered a major income loss than insiders, this difference drops to 18 percentage points in the continental and northern European countries of our sample.

Figure 3: Marginal Effects of Labour Market Status on Income Loss, in Peripheral and Core European Countries

To inspect the policy mechanisms that plausibly fuelled cross-country inequalities, we complemented the survey analysis with three case-studies to compare the distributive characteristics of the social policy measures implemented in Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands in the first wave of the pandemic.

In a nutshell, the case studies highlighted the following aspects. First, short-time emergency policy responses in countries with traditional insider-biased welfare arrangements further penalised outsiders. Most notably, Italy and Germany prioritised the strengthening of well-established policies that are mostly targeted at insiders, such as short-time work schemes (Kurzarbeit and Cassa integrazione). To be sure, the scarce administrative capacity of the Italian welfare system translated into a patchier response and delays in guaranteeing economic support (in particular) to the outsiders. At the same time, the high fragmentation and low generosity that characterised the pro-outsiders’ emergency measures in Italy remained consistent with the traditional welfare model of the country. Similarly, Germany, although enjoying higher administrative capacity, maintained the general dualisation of its employment policy system. However, it moved some steps closer to a more even welfare protection, by expanding more decisively the coverage and generosity of, for example, social assistance and universal child benefits. The very exception to the Bismarckian dualisation rule was the Netherlands, where the COVID-19 pandemic arguably accelerated a change that was already underway before the crisis (Cantillon et al., 2021), marking the definitive abandonment of insurance-based schemes such as STW in favour of non-contributory universalistic benefits, more accessible for outsiders.

In this regard, however, the Next Generation EU (NGEU) package could possibly be a game-changer.

Second, the comparison of the three cases reveals that the breadth of the fiscal space available to governments contributed to determine the size of the emergency responses, regardless of the strictness and length of lockdown measures and of the extent of the economic loss. Despite having been hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic, Italy, which was heavily indebted, did not deploy a fiscal response comparable to that of Germany. The overall size of the social policy response in Italy was more in the ballpark of that of the Netherlands, where, however, both containment measures and the ensuing economic slowdown had been considerably more modest. The state of the public budget seems to have been more relevant than the political colour of the government in determining the magnitude of the response. Although the centre-left Democratic Party and the Five Stars Movement – the main coalition partners of the Italian Conte II government – shared pro-spending policy positions, the Italian response was less extensive and generous than those in Germany or in the Netherlands, where government coalitions were led by more fiscally conservative centre-right parties.

Taken together, these considerations suggest bleak prospects with regards to future developments of the double dualisation of Europe. A few months after the outbreak of the COVID crisis, inequalities both within domestic labour markets and between core and peripheral European countries were already widening. Faced with an unexpected shock, not only governments adopted short-term social policy responses that by and large reinforced existing inequalities between labour market insiders and outsiders — with the notable exception of the Netherlands. In addition, this trend was even more marked in a peripheral country like Italy than in a core country like Germany. Regardless of the temporary suspension of the Stability and Growth Pact, the latter could count on a much more stable public finances, which allowed policy makers wider fiscal leeway to provide better social protection (also) to outsiders.

In this regard, however, the Next Generation EU (NGEU) package could possibly be a game-changer. The NGEU introduced a recovery fund of over €750 billion, including raising commonly issued debt to finance intra-EU temporary fiscal transfers. This shift towards greater fiscal risk pooling may smoothen fiscal disparities between the core and the periphery of the EU, and allow more room to economically weaker countries for coping with today’s socioeconomic challenges. In other words, by backing a stronger social policy response also in peripheral countries, the NGEU could help mitigate the ‘double dualisation’ trend. At the same time, its temporary nature raises concerns. While the European political compromise behind NGEU appears fragile, the double dualisation process affecting Europe seems structural in its nature. If the latter is not tackled seriously by post-COVID-19 inclusive growth strategies, increasing labour market divides and gaps in social protection may foster unpredictable political backlashes, as double dualisation provides a breeding ground for different forms of populism and Euroscepticism (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, 2022).

This blog post originally featured on EUVisions.