Stefano Ronchi and Joan Miró i Artigas

Based on a Research Article by Stefano Ronchi, Joan Miró i Artigas and Maurizio Ferrera

Full publication: ‘Walking the road together? EU polity maintenance during the COVID-19 crisis’, West European Politics, 44 (5-6): 1329-1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1905328

The dramatic socio-economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic reawakened the tensions between Northern and Southern member states that had already shaken the EU during the 2010s. Contrary to what happened during the euro crisis, in the COVID crisis the member states managed to reach an agreement in only about five months. How did EU leaders move past the deadlock of the euro crisis years?

The dramatic socio-economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic reawakened the tensions between Northern and Southern member states that had already shaken the EU during the 2010s. In April 2020, about two months after the COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy, the former President of the Commission, Romano Prodi, launched a passionate warning: if EU leaders could not find an agreement ‘even in such a dramatic situation, there [would be] no longer any basis for the European project’. The risk of a new ‘existential crisis’ was, however, successfully averted. Country leaders gradually converged towards the basic logic advocated by the President of the Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, i.e. that of addressing the crisis by ‘walking the road together’, without ‘leaving countries, people and regions behind’. The resulting compromise was the adoption of the Next Generation EU (NGEU) Plan in July 2020. It constituted an unprecedented step towards deeper fiscal integration, involving the undertaking by the European Commission of massive borrowing on the capital markets for the first time (€750bn) to provide grants (€390bn) and loans to member states. How did EU leaders move past the deadlock of the euro crisis years?

At the outbreak of the pandemic, the sharp North–South divide seemed intractable, especially on the issue of cross-national transfers. Initially siding with Northern governments, Germany gradually switched its position and came to endorse the solidaristic approach of the French government. This shift was key to tilting the balance of forces in favour of greater fiscal integration, not only due to Germany’s hegemonic position within Europe’s economy but also because it removed from the fiscally conservative coalition its most powerful actor. In the following we reconstruct how the inter-state conflict unfolded during the negotiations for the EU recovery fund and show why Chancellor Angela Merkel’s reversal was crucial to pave the way for the NGEU agreement.

The high degree of conflict perceived by citizens at the outbreak of the pandemic reflects the turbulent politics which unfolded in the EU public sphere.

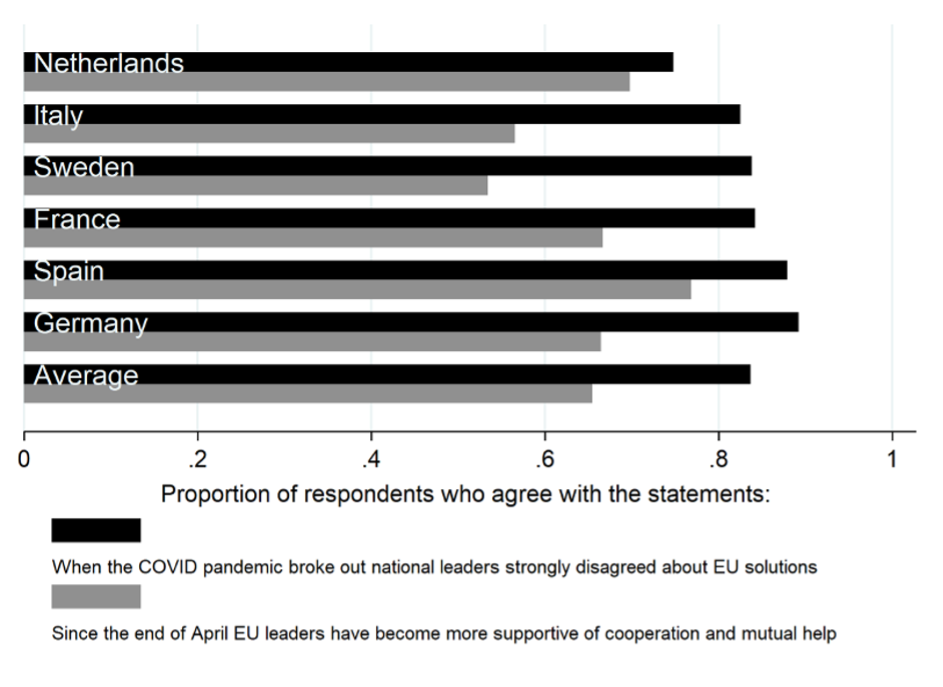

Contrary to what happened during the euro crisis, in the COVID crisis the member states managed to reach an agreement in only about five months (March–July 2020). The fast-changing parabola of the conflict surrounding crisis management was perceived by the European public. Figure 1 shows that the majority of citizens in six selected member states did note the shift from confrontation to appeasement. Interviewed in June 2020, a share of respondents ranging from 75 per cent in the Netherlands to 90 per cent in Germany recognised that, at the outbreak of the pandemic in March, national leaders were strongly divided on common European solutions. On average, about 65 per cent of respondents also agreed that since the end of April, EU leaders had become more committed to cooperation and mutual help.

Source. ‘The Economic and political consequences of the COVID-19 crisis in Europe’ survey, conducted in the framework of the SOLID research project financed by the European Research Council.

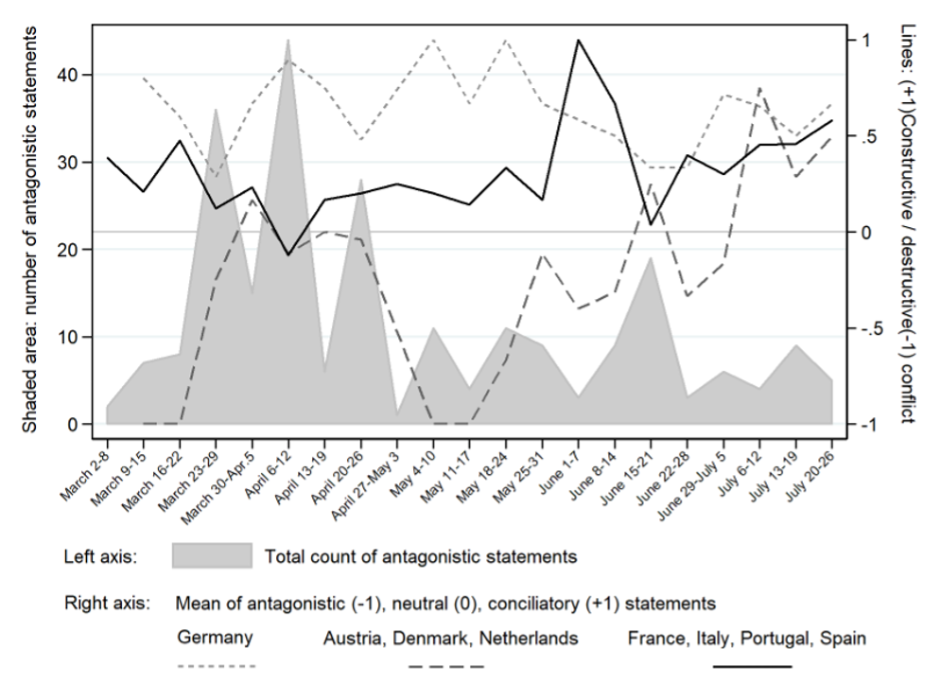

The high degree of conflict perceived by citizens at the outbreak of the pandemic reflects the turbulent politics which unfolded in the EU public sphere. In a recent contribution, together with Maurizio Ferrera, we reconstruct the dynamics of the inter-state conflict through an analysis of EU leaders’ direct quotes that appeared in a selection of both national and international newspapers between March and July 2020. We selected 19 leaders, including the heads of government and the finance ministers of eight EU states (Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Italy and France) plus the President of the European Commission von der Leyen and the European Commissioner for Financial Affairs Paolo Gentiloni. We coded leaders’ statements as ‘destructive’ (coded as -1) or ‘constructive’ (+1) based on the degree of antagonism as opposed to compromise-seeking attitudes they conveyed (neutral stances were coded as 0).

Figure 2 provides a bird’s-eye view of developments in line with the antagonism–conciliation conflict dimension. The shaded area indicates the weekly number of antagonistic statements (left-hand axis), thus helping to identify the peaks of the conflict. The lines show the evolution of the average tone of leaders’ quotes (right-hand axis) for three country groups: the three most outspoken ‘frugal’ countries (Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands), Southern countries, and France and Germany. This indicator is computed as the mean of antagonistic/conciliatory/neutral statements, ranging from -1 (when all claims were antagonistic) to +1 (all conciliatory claims, suggesting a ‘constructive’ attitude).

Figure 2 suggests three phases in leaders’ discourses. Initially, the debate in the media was dominated by Southern member states and France, which, being more affected by the COVID virus, were vocally calling for solidarity. Their calls, however, initially remained unheard. Germany and the other frugal countries only entered the media debate in mid-March. A second phase goes from late March to the end of April. In this period, the COVID crisis hit the headlines throughout Europe: everyone was affected, and the economic repercussions of lockdowns became a shared concern. The ‘destructive’ peak of the conflict was reached soon after the European Council meeting of March 26. Cross-country contrapositions became barefaced, emblematically brought into the spotlight by the quarrel between the Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra and the Portuguese PM António Costa. The week of April 6–12 registered the highest number of antagonistic statements on both sides. Remarkably, at the peak of the conflict Germany went against the tide, maintaining a conciliatory tone (fine-dashed line in Figure 1).

Antagonism across the North–South divide continued until the Council meeting of April 23, when state leaders reached an agreement that started to pave the way for a shared EU recovery plan. After that, a third phase can be identified, whereby the conflict surrounding policy responses to the crisis gradually became less harsh. The total number of antagonistic statements reported by the press decreased (shaded area in Figure 1), and the general mood veered towards more constructive and conciliatory relationships (upward trend of the lines). Since the beginning of May, the ‘frugals’ were less present in the media, although their very few public statements remained mostly antagonistic (thus the slump of the dashed line in Figure 1 at the beginning of May). However, afterwards, they also gradually shifted towards a more constructive position. Hardly any antagonistic statement came from Germany, which adopted a conciliatory tone throughout the whole period.

On the other side, the ‘frugal four’ insisted on national responsibility by favouring the use of existing crisis resolution mechanisms, conditionality and loans.

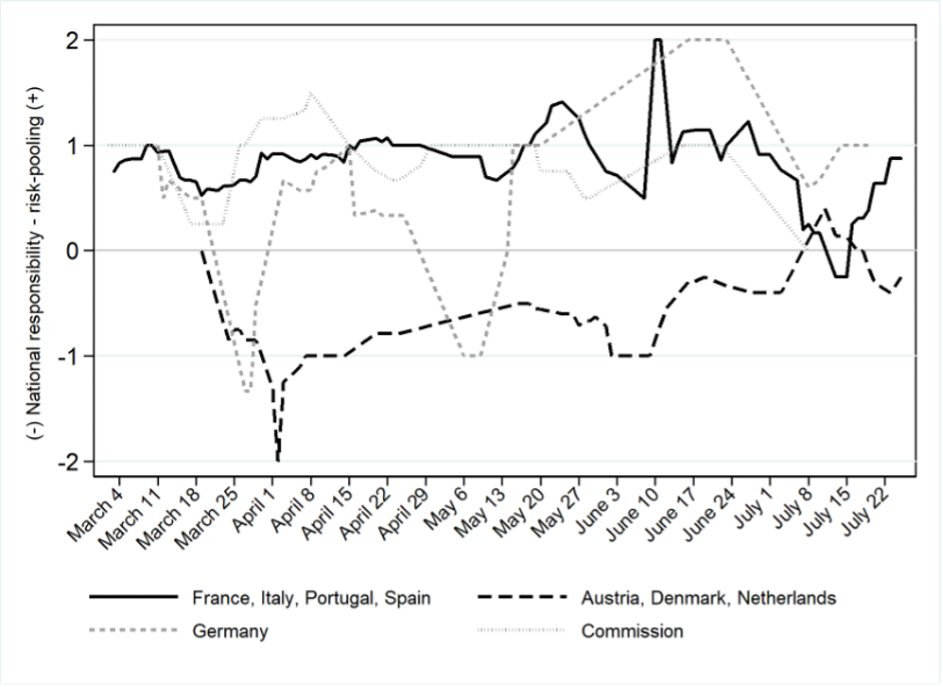

Figure 3 illustrates the developments along another crucial dimension of the inter-state conflict, i.e. policy positions regarding the pooling of fiscal risks. In this regard, we coded policy-related leaders’ quotes along an ordinal measure in which the value (+1) indicates support for greater risk sharing, the value (-1) shows opposition to greater risk sharing and the value (0) indicates a neutral or absent evaluation on the issue. For example, in the debate on the establishment of temporary fiscal transfers, we have assigned a value of (+1) to those opinions defending grants and (-1) to those defending loans.

Data shown in Figure 3 confirms that the second phase (late March/April) was characterised by high polarisation of policy preferences. On one side, Italy, France, Portugal and Spain advocated high-risk-pooling policy responses, such as the flagship proposal of ‘coronabonds’. On the other side, the ‘frugal four’ insisted on national responsibility by favouring the use of existing crisis resolution mechanisms, conditionality and loans. In this phase, Germany oscillated between the two poles, siding with the ‘frugals’ in opposing coronabonds but repeatedly calling for European solidarity. Such oscillations reflect the initial divergence between Merkel, sceptical towards the option of issuing joint debt, and Olaf Scholz (Finance Minister in the German coalition government), who since the beginning of the crisis had been sympathetic towards that option and played an important role in orchestrating a compromise with France. The position of Germany coalesced around a pro-risk-pooling stance by the middle of May, that is, when Merkel put forward the Franco-German plan together with French President Emmanuel Macron (May 18), laying the foundations for the Commission proposal, which was presented a week later.

Germany and France certainly took the lead in devising a first blueprint for a compromise. While President Macron and his Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire were firm on their pro-risk-pooling stance, Germany shifted from siding with the ‘frugals’ to promoting solidaristic policy options. Despite this notable change in policy positions, German leaders avoided destructive-conflictual tones and played a key role as mediators. While Scholz had been leaning towards EU-solidaristic solutions since the very beginning, the crucial actor in the shift, ultimately tilting the European balance, was Merkel, the Christian-Democratic Chancellor.

This shift towards more fiscal solidarity had to be justified to national publics, first of all in Germany. Therefore, the symbolic communication of Merkel was crucial, and it served the dual aim of keeping the member states together while selling the new policy compromise to German voters. The most emblematic example of this effort can be found in the speech given on April 23 in front of the Bundestag, a few hours prior to the European Council meeting that sealed reconciliation after the first phase of conflict. Here Merkel cautiously brought up the issue of German interest vis-à-vis the EU by saying, ‘For us in Germany, the commitment to a united Europe is part of our reason of state. […] We are a community of fate’. And she concluded the speech with a passionate plea for a European Germany: ‘What applies to Europe is also the most important thing for us in Germany’.

This blog post originally featured on EUVisions.