Joan Miró i Artigas

Based on a Research Article by Joan Miró i Artigas

Full publication: ‘Responding to the global disorder: the EU’s quest for open strategic autonomy’, Global Society, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2022.2110042

The SOLID project studies how the EU evolves in reaction to existential crises. It examines the policy responses to crises, as well as the politics of the crisis management. But its differential element is the focus on the polity implications of deep crises: why and in which ways certain dislocations (such as the euro crisis, Brexit, or the refugee crisis) become threats to the foundations –in terms of territorial boundaries, authority structures, and solidarity mechanisms– of European integration, and how the attempts to address these dislocations end up modifying (possibly strengthening) these very foundations.

Crises are a timely topic to study, of course. Polycrisis was selected as one of the words of 2022 by the Financial Times (Derbyshire 2023). But before Adam Tooze (2021) popularised the term in its Shutdown, polycrisis was already a trendy concept in EU studies, conventional knowledge saying that it was first employed by former Commissioner President Jean-Claude Juncker to refer to the convergence of challenges that the Union faced between 2010 and 2016.

Although not having the character of a highly urgent problem that calls for swift action usually associated with crises, the recent existential troubles of the liberal international order add to the sense that we are in a historical period of upheaval and transformation. In a recent article I have published in Global Society, I argue that the deep transformations that the global order has been facing since the Great Recession represent a fundamental challenge for the EU, possibly more than for any other polity. Over the last decades, the EU has embodied the most ambitious project of supranational integration in the world, incarnating in its own architecture both the Wilsonian aspiration of a rules-based global order as well as the Hayekian ambition of liberalisation through international integration. As such, the EU has not only developed, internally, into the world’s most integrated trade area, but has also, externally, become a long-time champion of free trade and multilateralism on the global stage, with the European single market being one of the most open economies in the world. The extent to which greater market liberalisation became the raison d’être of the EU is shown by the fact that any sign of dirigisme and “economic patriotism” came to be perceived as a dangerous affront to European integration (Rosamond 2012). Globalisation – as a political and ideational paradigm – influenced in sum both the EU’s internal and external agendas, and in fact, it merged them.

Not surprisingly therefore, the current transformation of globalisation is generating new challenges for European integration in ways that are potentially at odds with the neoliberal rationale that dominated since the years of the Single European Act. The persistent trend towards the geopoliticisation and weaponization of trade relationships, the ongoing decoupling between the US and China, the spread of protectionist measures, the declining influence of global institutions of multilateral governance such as the WTO’s Appellate Body; and more recently, the Russian aggression against Ukraine, are all tensions that calling for a rethinking of the EU’s long-established understandings of both international and European integration.

‘Open strategic autonomy’ has emerged as a key concept in this process of rethinking. At its core this idea indexes a preoccupation with unduly vulnerabilities of Europe’s economy to supply chain disruptions, third-country dependencies, and geopolitical risks, and a consequent drive for greater European self-reliance in a range of policy fields (European Commission 2021). As such, strategic autonomy is a mindset or discourse deeply intertwined with that of European sovereignty. According to Charles Michel, European Council President, “European strategic autonomy is goal number 1 of our generation […] the strategic independence of Europe is our new common project for this century”.

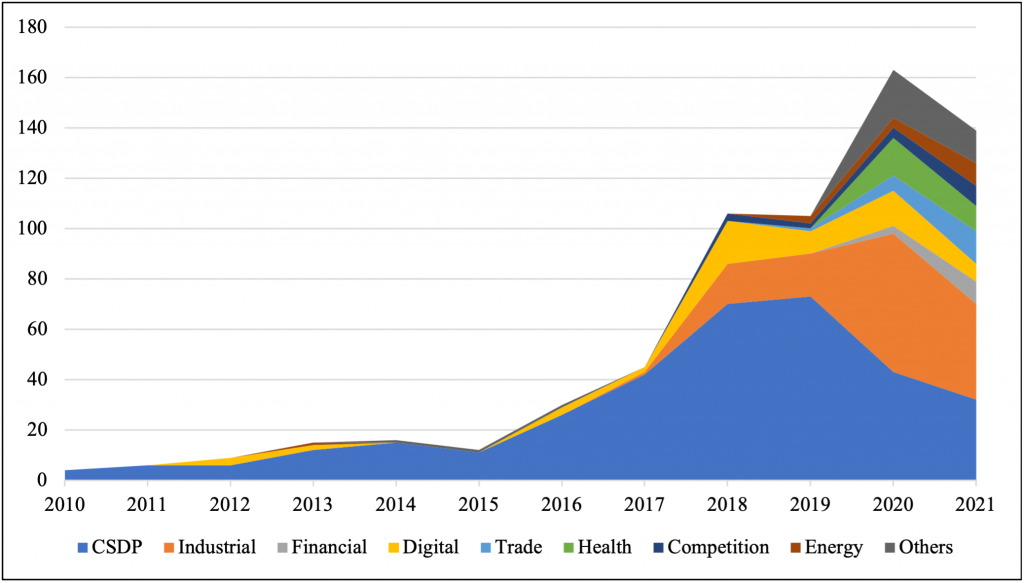

As shown in Figure 1, although having its origins in defence policy, strategic autonomy has become, in the last years, a ubiquitous concept in several policy fields, finding its way into the domains of industrial, trade, telecommunications, energy, climate, agricultural and even financial and monetary policy.

Source: Publications Office of the European Union. Author’s own graph.

In the Global Society article, I argue that the most impactful consequences of the strategic autonomy debate will not be in the defence policy domain in which it was born, but in trade, industrial, competition and digital policy. Between 2019 and 2023, the EU has approved a range of new trade defence instruments, such as the Framework for the Screening of Direct Investments in the Union, the Regulation on Foreign Subsidies in the Internal Market, the so-called anti-coercion trade defence instrument, the Single Market Emergency Instrument, an International Procurement Instrument (IPI), or Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (still in discussion), that indeed mark a shift towards a more defensive and assertive trade posture. In the area of industrial policy in turn, in contrast to the focus on horizontal interventions that had defined the EU’s approach in the last decades, the strategic autonomy push is fuelling a more active and interventionist approach to industrial policy, the European Chips Act, the revision of the framework on Important Projects of European Interest (IPCEIs), or the Critical Raw Materials Act being some of its first concrete outputs.

Overall, and in spite of mainstream integration theories’ traditional neglect of the interactions between global capitalism and European integration, the relationships between both domains concern not only on the external policy domains of the EU, but also in its internal ones, and have important implications for the political economy of EU-level state intervention. Thus, despite having emerged as a concept which aims to rethink the EU’s relationships with the outside world, the strategic autonomy debate is powering new understandings about the internal organisation of the EU polity. A prerequisite for achieving greater strategic autonomy is indeed a greater capacity to act collectively.

In this sense, it is my expectation that in an international scenario increasingly marked by uncertainty and conflict, strategic autonomy will remain a central topic in discussions about the future of the EU. As the emerging state-building literature on EU integration argues, in contrast to the predominant market-based motivations that have historically push forward European integration, the emergence of collective security imperatives in EU politics may well result in pressures for greater centralisation or coordination of political authority (Kelemen and McNamara 2022).

Derbyshire, J. (2023) “Year in a word: Polycrisis”, Financial Times, January 1. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/f6c4f63c-aa71-46f0-a0a7-c2a4c4a3c0f1

European Commission (2021) “Strategic Foresight Report 2021.” COM(2021)750, September 8.

Kelemen, R. D., and K. R. McNamara (2022) “State-building and the European Union: Markets, war, and Europe’s Uneven Political Development”, Comparative Political Studies 55(6): 963–991.

Miró, J. (2022) “Responding to the global disorder: the EU’s quest for open strategic autonomy”, Global Society.

Rosamond, B. (2012) “Supranational Governance as Economic Patriotism? The European Union, Legitimacy and the Reconstruction of State Space”, Journal of European Public Policy 19(3): 324–341.

Tooze, A. (2021) Shutdown, New York: Viking/Penguin.